The Curious Physics of Slime Volleyball

2D Bouncing Balls Physics Tutorial (Elastic Collision)

This post will explore the classic game Slime Volleyball and some of its physics, notably 2D ball elastic collision.

It will go over:

- Some history of Slime Volleyball and how it's being used by cutting edge deep learning AI researchers

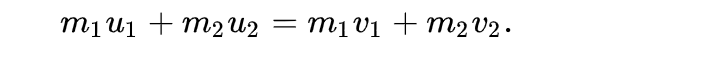

- How Conservation of Momentum and Conservation of Kinetic Energy serve as the underlying equations for the calculations

- Some practical tips on how to understand it intuitively, how to code it in up in a 2D game, and how the game physics diverges from real world physics

This post was created while writing an implementation of Slime Volleyball in Go using SDL 2.

Background

Slime Volleyball was a viral Java applet game that emerged around the year 2000, and I have many fond memories of playing it as a kid. I was watching Francesc Campoy's excellent just for func video series where he coded up a Go version of Flappy Bird, and I wanted to follow along with a different game, so I chose Slime Volleyball. However, when I got to the collision of the ball and the slime, I realized that I didn't understand how to correctly code it. So I started looking at some other implementations and tried to learn a little more about how the calculations are derived.

One option would be to just reach for a physics engine like Box2D, but I wanted to learn more about the underlying physics, wanted to be able to tweak it more easily, and I didn't want to bring in a big dependency for what was ultimately just a few lines of code.

In most games, it's not super critical that the game physics closely match real world physics, and you often intentionally diverge from them either out of practical necessity or as an intentional part of the design. However, as humans we do have some intuition for how things work in the "real world" so having at least some understanding of how the real physics work is a good baseline to start from. Slime Volleyball physics both use some simplifications, some "fudge" factors, and then one major divergence from real world physics which I will review.

Along the way reviewing other implementations, I stumbled upon hardmaru, a Google Brain researcher that uses Slime Volleyball to compare reinforcement learning algorithms.

Like Bitcoin, the original creator of Slime Volleyball is unknown, though at least one version was maintained by Quin Pendragon and Daniel Wedge. Reddit user /u/marler8997 decompiled the Java applet and rewrote it in Javascript for an HTML5 version which I used as a reference for my Go version. However, his collision physics code isn't exactly easy to understand.

function collisionBallSlime(s) {

var dx = 2 * (ball.x - s.x);

var dy = ball.y - s.y;

var dist = Math.trunc(Math.sqrt(dx * dx + dy * dy));

var dVelocityX = ball.velocityX - s.velocityX;

var dVelocityY = ball.velocityY - s.velocityY;

if(dy > 0 && dist < ball.radius + s.radius && dist > FUDGE) {

var oldBall = {x:ball.x,y:ball.y,velocityX:ball.velocityX,velocityY:ball.velocityY};

ball.x = s.x + Math.trunc(Math.trunc((s.radius + ball.radius) / 2) * dx / dist);

ball.y = s.y + Math.trunc((s.radius + ball.radius) * dy / dist);

var something = Math.trunc((dx * dVelocityX + dy * dVelocityY) / dist);

if(something <= 0) {

ball.velocityX += Math.trunc(s.velocityX - 2 * dx * something / dist);

ball.velocityY += Math.trunc(s.velocityY - 2 * dy * something / dist);

if( ball.velocityX < -MAX_VELOCITY_X) ball.velocityX = -MAX_VELOCITY_X;

else if(ball.velocityX > MAX_VELOCITY_X) ball.velocityX = MAX_VELOCITY_X;

if( ball.velocityY < -MAX_VELOCITY_Y) ball.velocityY = -MAX_VELOCITY_Y;

else if(ball.velocityY > MAX_VELOCITY_Y) ball.velocityY = MAX_VELOCITY_Y;

}

}

}

What is something variable supposed to be? I will review that now:

Elastic Collision Physics

The main concept to understand the bounce is Elastic Collision. This means a collision with no loss of energy. In the real world there would be some friction and loss of energy, but we can ignore that in our slime world. In an elastic collision, two equations apply, the Conservation of Momentum and Conservation of Kinetic Energy (this one only applying in elastic idealized collisions). The Conservation of Momentum states that:

and the Conservation of Kinetic Energy states that:

Now what you can note is that, since we can assign whatever masses to our two circles that we want, and we know their initial velocities, there's only two unknowns, which are the two final velocities. And we have two equations, and two unknowns, so we can solve for those two unknowns.

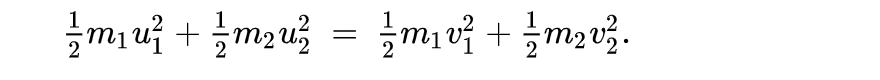

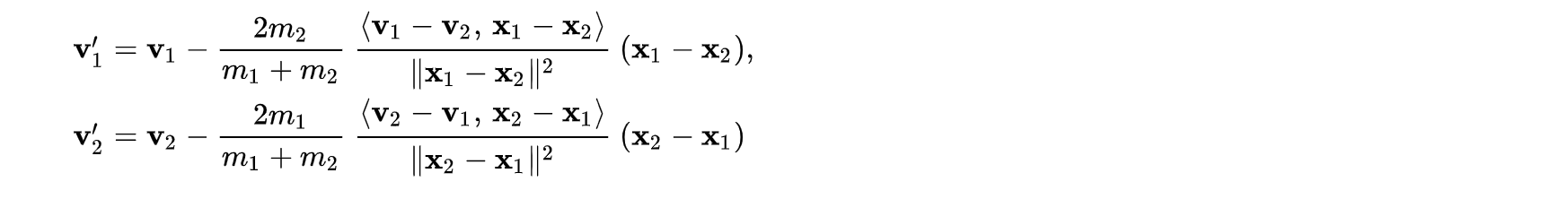

However, the actual algebraic derivations are quite tricky, so we can take Wikipedia's word for it and use their final equations, particularly the "angle-free" equations which use dot-product calculations instead of using trigonometry on the angle of the collision:

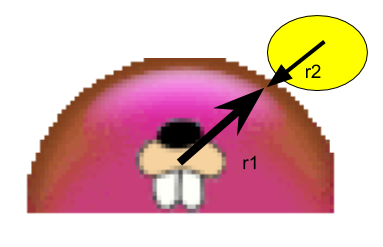

In our case, the slime is x1 with velocity v1 and mass m1, and the ball is at position x2 with velocity v2 and mass m2.

A helpful note, in this case x1 and x2 are the position values, which each have an (x,y) component. This (x,y) component represents the center of the circle (the slime itself is represented as a circle with the bottom half not rendered).

The parentheses in the Wikipedia equation represent the dot product, so we are taking the dot product of the difference in positions of the two circles and the difference in velocities, across the x-axis and y-axis. In the code this is represented by:

(dx * dVelocityX + dy * dVelocityY)

There's a few important takeaways from the "angle free" collision equation. Our new velocities are based on the initial velocities with some change. The change of the ball velocity has three terms.

- The first term is based on the ratio of the masses

(2m1/(m1+m2)). This will simplify to just2. - The second term is a dot product divided by a distance. This will be a scalar value.

- The third term is the vector difference of the two positions

(x2-x1). This will be a vector value.

Importantly, the first two terms are scalar values (just a magnitude with no direction), while only the third term has a vector value.

We can simplify things by making the slime mass m1 set to 1, and the ball mass m2 set to infinitesimal (rounds to 0), as if the slime has much more mass. This leaves the slime velocity unchanged, v1 = v1, since the velocity change is multiplied by the mass m2=0. This is a good simplification for the game since we don't want the slime itself to bounce.

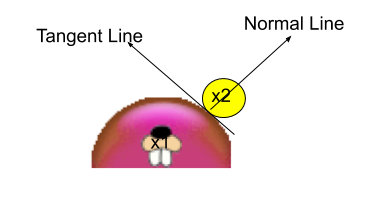

The direction of the ball's velocity change is determined by the final x2-x1 component, which is the vector difference between the two positions. That is also called the "normal" component of the collision, since it's in the direction perpendicular to the tangent line between the two circles.

So now we know the direction of the force we are applying, we just need to know how much force we need to apply (the magnitude).

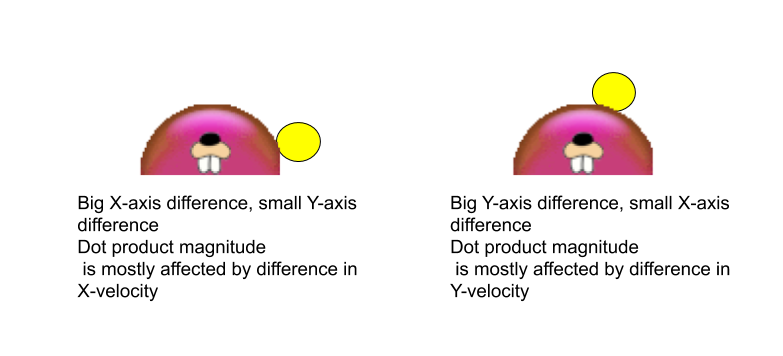

As mentioned, the first term, the ratio of the masses, should simplify to 2, so we just need to calculate the dot product of the position difference with the velocity. This is basically where the angle of the collision gets taken into account, as the dot product is a simpler way to write the product of the magnitudes and the cosine of the angle.

Again, in the code this looks like:

(dx * dVelocityX + dy * dVelocityY)

So the closer to the top of the slime hits, the more the ball will be affected by the y-velocities, and the closer to the edge of the slime the ball hits, the more the ball will be affected by the x-velocities. This also aligns with our intuitive understanding of how the physics "should" work.

The final part of the equation is dividing by the distance between the two velocities, squared. In physics, it's very common to divide a vector by a distance to "normalize" it, which turns a vector into a distance of 1. This makes sense for when you're trying to calculate a direction without having the raw magnitudes affect the end result. My way of thinking about dividing by the distance squared is both the second (the dot product) and third terms (the direction) are being normalized, so only the relative masses affect the end calculations.

Tying back to the HTML5/Javascript implementation, it's now clear that the something variable is the dot product value in the Wikipedia elastic collision equation, though normalized ahead of time.

Coding The Physics In The Game

In this last part, we will review some practical tips on implementing the "bounce" in the code.

The first important step is detecting the collision itself. Fortunately, this is super simple, as we represent both the ball as a circle, and the slime as a circle (the bottom half is simply not rendered). Since both circles have a radius, we can decide the ball collides with the slime if the distance between the two circle centers is less than or equal to the sum of the two radii.

Once the collision is detected, you don't want to apply the calculations right away. This is because if you change velocity, but in the very next frame the ball is still colliding, the velocities will be recomputed again based on the new post-collision velocities, which won't be right and may create the ball to get stuck in some weird loop. So instead, once the collision is detected, we first move the ball away from the slime so that it's no longer colliding and then calculate the new velocities.

ball.x = s.x + Math.trunc(Math.trunc((s.radius + ball.radius) / 2) * dx / dist);

ball.y = s.y + Math.trunc((s.radius + ball.radius) * dy / dist);

Another detail that the HTML5 version applies is capping both the new x and y velocities at a maximum value. While this shouldn't be strictly necessary, it keeps the game more even paced and avoids a strange collision sending the ball rocketing.

As another adjustment, while in the "real" physics calculations our mass ratio term was 2, in the game we can basically consider this a fudge factor to be whatever we want so that the game feels fun and natural.

Finally, both the HTML5 version and hardmaru's Python version make one significant divergence from true elastic collision physics. That is, during the collision when calculating the new velocities, they also add the slime's current velocity to the new ball velocity. In the actual elastic collision detections, the slime's velocity only plays a role in that the difference between the slime's velocity and the ball's velocity contribute to the dot product magnitude of the change.

What's the impact of this divergence from real physics? The main impact is that the ball becomes a bit more controllable by the slime. For example, it's easier to "catch" the ball by moving the slime backwards as the ball is coming towards it. If the physics calculations stuck to the real world, the ball's velocity would bounce forward and fall and hit the ground. By also adding the slime's velocity to the new velocity, the ball "sticks" the slime and moves with it, giving the player more fine-tuned control of the ball and letting the player make more surprising moves.

Conclusion

These days, most game developers use engines like Unity 3D that come with pre-packaged physics solutions, so you don't need to learn about these topics to make a game. Still, creating a game from scratch with a minimalistic 2D layer like the HTML5 Canvas or libsdl allows you to learn a lot of interesting graphics, physics, and AI concepts from first principles. I had fun recreating one of my favorites games and learning from other implementations, and I hope this article might help anyone stuck on 2D game physics in the future.